Town Center Walk

Shimonita Geopark Guidebook

Welcome to Shimonita Town

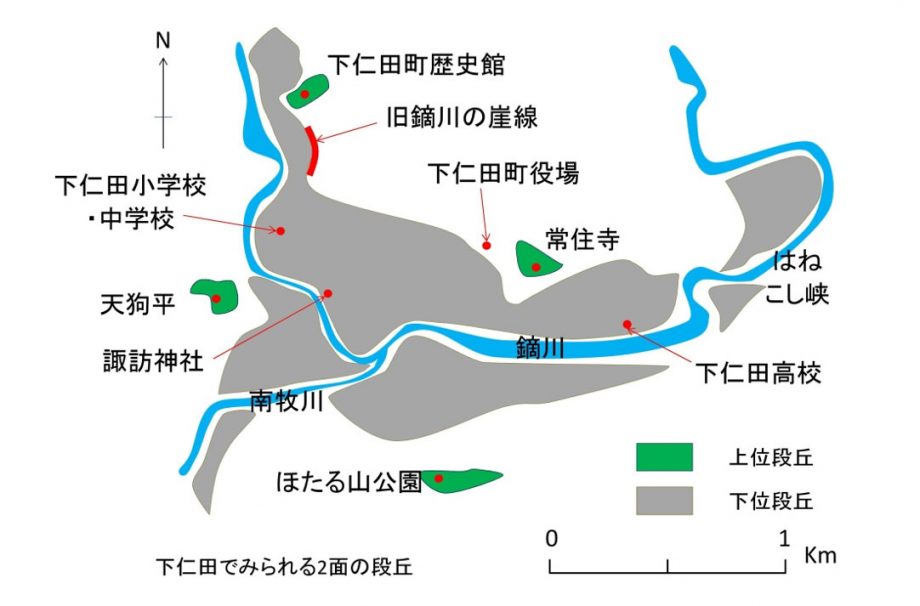

Shimonita is a small basin measuring about 2 km from east to west and 1.5 km from north to south, surrounded by mountains.

To the east, the Kanto Plain stretches out downstream of the Kabura River, which flows from Mt. Mayama, while to the west lie the mountain ranges along the border of Gunma and Nagano Prefectures.

People have lived in the Shimonita area since the Paleolithic era. The Shimonita Road, once a side route of the Nakasendo highway, flourished as a route for ordinary people and a hub for relaying goods, linking Joshu (modern-day Gunma) with Shinshu (modern-day Nagano). It also served as a cultural crossroads.

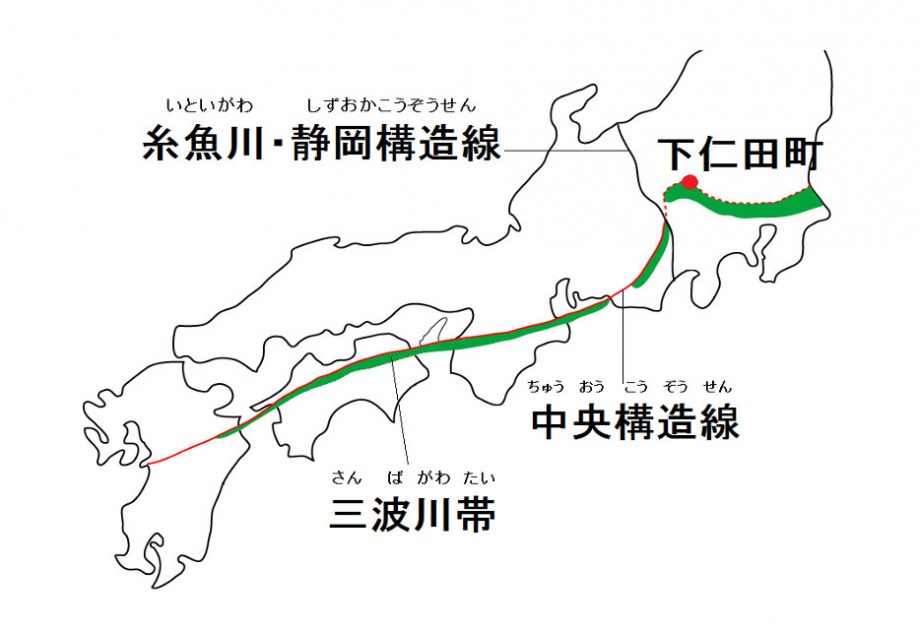

Traces of history remain throughout the town, such as the Suwa Shrine, known for its carvings, and scars from the Battle of Shimonita at the end of the Edo period. Additionally, the Median Tectonic Line, which divides the Japanese archipelago east to west, runs through the town. This makes it a geological treasure trove, where you can observe strata and rocks from various geological periods.

Let’s start our walk from Shimonita Station and explore the sights of downtown Shimonita.

Mountain Passes at the Gunma–Nagano Border

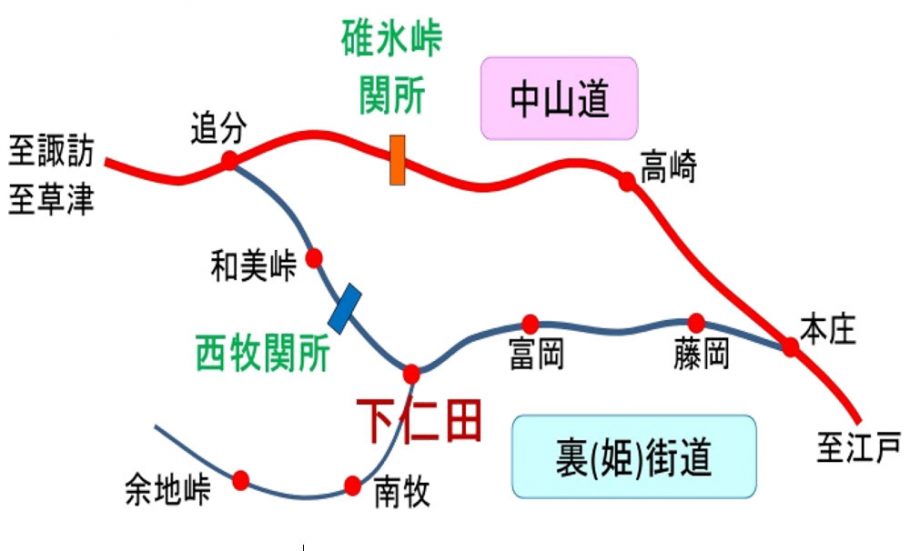

The Shimonita Road entered Joshu from Honjo-juku in Bushu (now Saitama Prefecture) and passed through Shimonita to connect with Oiwake-juku in Shinshu.

Compared to the main Nakasendo highway, which had strict checkpoints like Usui Barrier and steep climbs such as Usui Pass, the Wami Pass was a gentler mountain road. It was popular among ordinary people and merchants as a more accessible route.

There were several mountain passes connecting Shimonita with Shinshu, and they developed as major routes for the exchange of goods between east and west.

1. Jōshin Railway – Shimonita Station

The gateway to Shimonita by rail

The terminal station connecting Takasaki and Shimonita

In 1884 (Meiji 17), the Nippon Railway Company, a private enterprise, opened the Ueno–Takasaki line, marking the arrival of railroads in Gunma Prefecture. The predecessor to the current Jōshin Railway, called the Kōzuke Railway, was also privately funded and completed the full line between Takasaki and Shimonita in 1897 (Meiji 30).

One of the “100 Best Stations in the Kanto Region”

Shimonita Station was selected in 1999 (Heisei 11) as one of the top 100 stations in the Kanto region, as part of the 3rd annual “Railway Day” celebration.

Jōshin Electric Railway Co., Ltd.

In 1921 (Taishō 10), a plan was drafted to extend the line from Shimonita over Iwado and Yojitōge passes to Haguroshita Station on today’s Koumi Line. The railway was renamed the Jōshin Electric Railway Company.

In 1924 (Taishō 13), the entire line was electrified, and in 1964 (Shōwa 39), it officially became the Jōshin Railway Company, as it remains today.

Kōzuke Railway

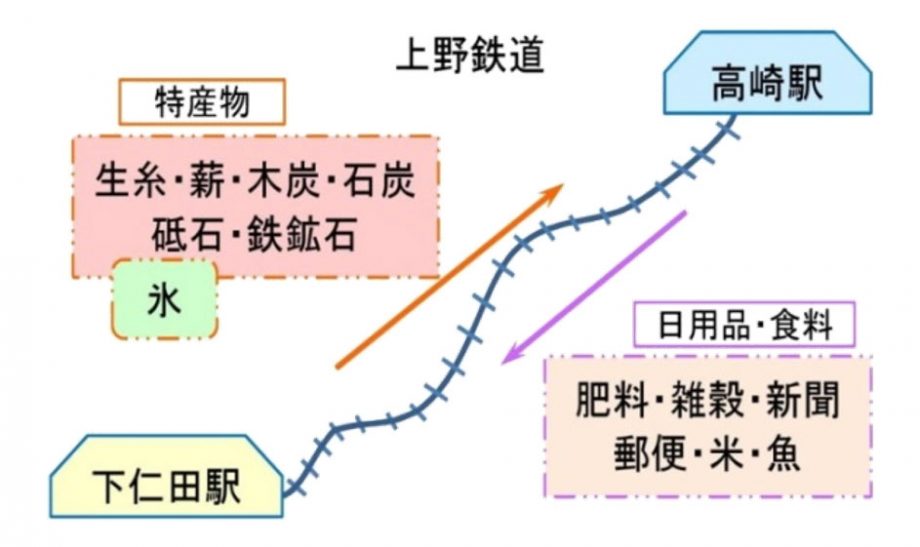

When the Kōzuke Railway opened, goods like fertilizer, grains, newspapers, mail, rice, and fish were transported from the Takasaki area, while specialties from the Shimonita area included raw silk, firewood, charcoal, lime, whetstones, and iron ore.

In 1899 (Meiji 32), an ice plant was built in the Ōgui area of Shimonita, making ice another product shipped out from the region.

2.Honsei-ji Temple

Honsei-ji Temple is the burial site of two warriors who died in the Battle of Shimonita—Naka Tsugusai and Fujikichi Kubota, members of the Mito Tengu Party.

3. Former Headquarters of the Mito Tengu Party – Sakurai Residence

During the Battle of Shimonita, the Sakurai Residence served as the main base of operations for the Mito Tengu Party.

The current building was reconstructed after a fire in 1917 (Taishō 6).

The Tengu Party established its headquarters in the home of Yagobei Sakurai, where the commander-in-chief Kōunsai Masao Takeda Iganokami and 10 other senior members stayed.

Other members were quartered in auxiliary headquarters, such as the homes of Gorōbei Sugihara, Yaemon Sakurai, Magobei Wakisaka, Yasue Ariga, Denemon Tominaga, Hanjūrō Sugihara, and Sōbei Ariga.

Shimonita Battle

On the early morning of November 16, 1864 (Genji 1), a fierce battle broke out in the Kosaka area of Shimonita between the Mito Tengu Party, a group of Mito loyalists seeking to uphold the imperial cause and expel foreign influence on their way to Kyoto, and the Takasaki Domain forces, acting under orders from the Tokugawa Shogunate.

The Tengu Party numbered 925 warriors, while the Takasaki forces had just over 200 men, yet the fight remained evenly matched for some time. Ultimately, the Tengu Party launched a three-pronged surprise attack, forcing the Takasaki troops to retreat from their headquarters.

In this intense clash known as the Shimonita Battle, 36 samurai of the Takasaki Domain and 4 members of the Tengu Party lost their lives in a tragic and heroic confrontation.

4. Grave of Ushinosuke Nomura & Monument “The Heroic Spirit Shines for Eternity”

Ushinosuke Nomura, a 13-year-old Mito warrior, fought in his first battle during the Battle of Shimonita. He was skilled in the Ono-ha Ittō-ryū sword style but suffered a serious wound after encountering Takahashi domain warrior Gihachi Naitō, who severed his right hand.

Fearing he would become a burden, Nomura is said to have committed seppuku (ritual suicide). A death poem was reportedly found near the collar of his body:

“Though my body soon returns to the soil,

My soul shall remain, protecting the realm.”

5. Takasaki Domain Main Camp – Satomi Residence

During the Battle of Shimonita, the Takasaki Domain entered the town via the Umezawa Pass and established their main camp in front of the Satomi Residence.

The Tengu Party launched a surprise attack from three directions: the main force advanced straight toward the camp, while others flanked via the ridgeline from Iseyama and attacked from across the Kabura River.

Using the terrain to their advantage, the Tengu Party succeeded in defeating the Takasaki forces.

Bullet marks from the battle can still be seen on the Satomi family storehouse.

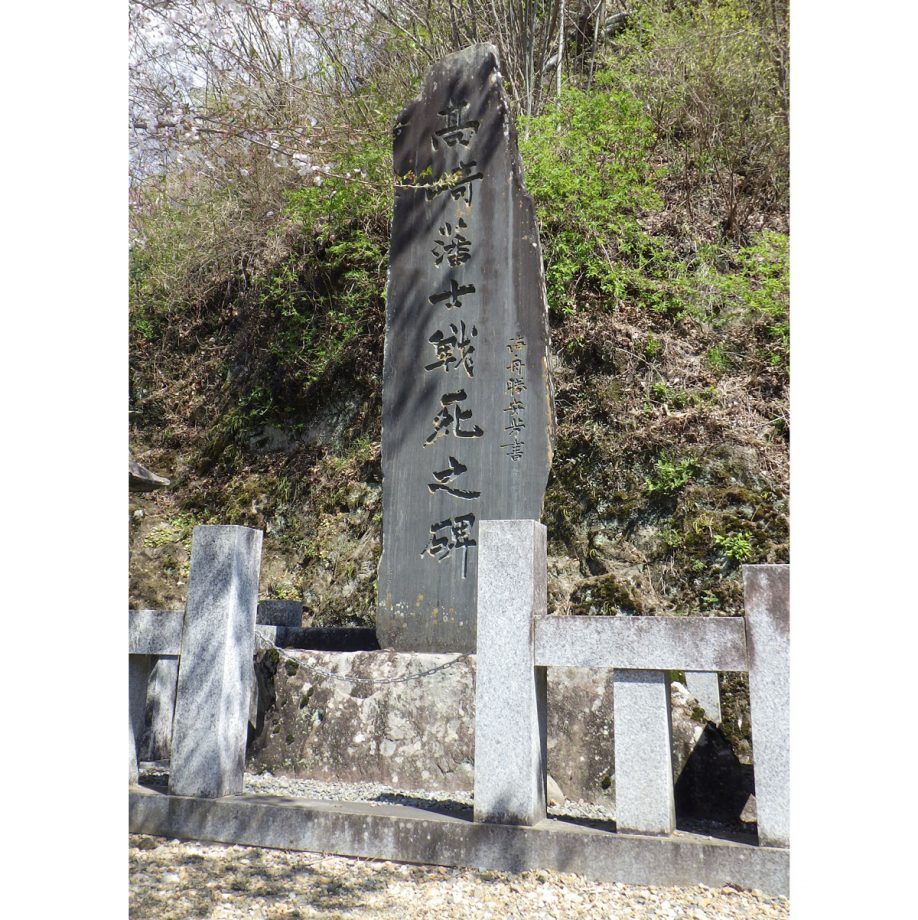

6. Monument to the Fallen Warriors of the Takasaki Domain – Shimosaka Iwashita

In 1893 (Meiji 26), on the 30th anniversary of the Battle of Shimonita, the “Monument to the Fallen Warriors of the Takasaki Domain” was erected at Shimosaka Iwashita.

The inscription was personally written by Kaishū Katsu, a prominent naval officer and statesman of the Meiji era.

7. Shimomachi 8. Nakamachi 9. Asahicho 10. Kamimachi

Shimonita in the Edo Period

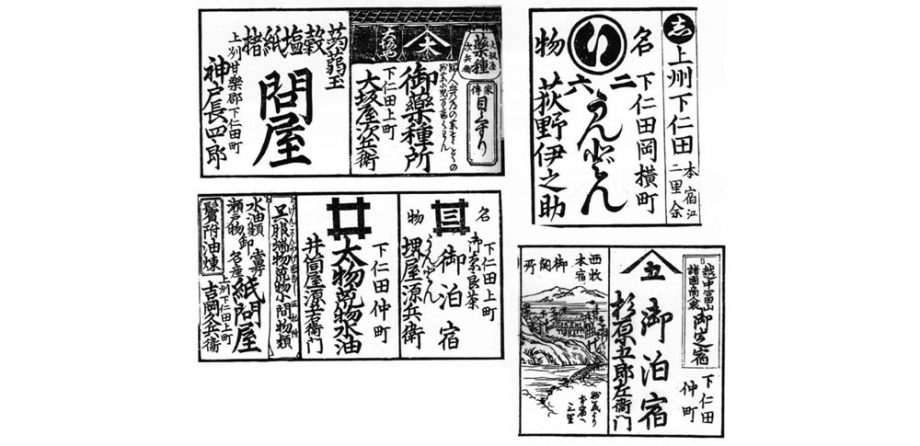

The Shimonita Road was widely used by commoners and merchants. In the town center of Shimonita, a market called the Kusai-ichi was held. It took place nine times each month on the 2nd, 5th, and 9th days, and was always bustling with people. Even today, versions of these markets remain, such as the Spring Market along the mountain, the Doll Festival Market (Hina-ichi), and the Year-End Grand Market.

The area was home to wholesalers dealing in high-quality hemp from western Jōshū, which they traded with Edo (Tokyo), Etchū (Toyama), and Gōshū (Shiga). There were also rice merchants dealing in rice from Saku, Shinshū (Nagano), and other merchants handling wheat, mixed grains, silk, paper, firewood, and daily necessities.

Kamimachi was located near the Kabura River, the central area was Nakamachi, and the most mountain-facing roadside area was Shimomachi. Okayokocho marked the border between Asahicho and Kamimachi.

Asahicho(Okayokocho): Udon shop (1 shop)

Kamimachi: Konjac merchant, pharmacy, paper wholesaler, lodgings (4 shops)

“Merchants’ Guide on Roads Throughout the Provinces”

Shokoku Dōchū Akindo Kagami

Published in 1827 (Bunsei 10) by the publisher Seiundo.

It features seven shops from Shimonita and sketches of the barrier station in Saimoku.

(From Miyama Bunko, Vol. 117)

Reasons Shimonita Village Flourished

- The road from Shimonita to Edo was well developed.

- There were numerous easily traversable mountain passes to Shinshū (Nagano).

- It was directly connected to the Hokkokukaidō and the Saku-Kōshū route.

- These routes were all sub-roads (*wakiōkan*), so travel regulations were relatively lax, making transportation more convenient.

Important Whetstones from the Nammoku Domain

Since the early Edo period, whetstones from Tozawamura were mined under direct shogunate control.

To transport these whetstones to Edo, the Shimonita Road was used.

Initially, they were shipped directly from Tozawamura to Tomioka, but later a relay hub, the To-kaisho (whetstone wholesaler), was established in Shimonita, greatly contributing to the town’s development.

Chūō-dōri, Reminiscent of the Town’s Former Prosperity

Chūō-dōri was once called Ōten Yokochō (Tenno Alley) and flourished as an entertainment district.

Because of its narrow width, it remains a pedestrian-priority street, preserving the mid-Shōwa atmosphere.

Even today, the Tanabata Festival is held here in summer, organized by the local Tanabata Committee, and in early November, the “Ittenbē Festival”, organized by the community development committee, enlivens the area.

Billiards Hall

Though the interior is no longer visible, this billiards hall once featured a pocketless billiard table for “four-ball”, a rare sight in modern Japan.

11. Aoiwa Park

The greenish rocks that make up Aoiwa Park are formed from black basaltic lava and tuff that erupted from a submarine volcano and accumulated over time. When these rocks were pushed deep underground, heat and pressure transformed them into green metamorphic rock. Their distinct characteristics include their green color and their tendency to split in one direction.

Aoiwa (Greenstone)

The stone pavement that stretches through the park features Sanbagawa schist, a type of crystalline schist from the Kanna River, and is one of the representative rocks of the Sanbagawa Metamorphic Belt. This belt stretches from Mt. Mikabo in the east-southeast, across Saitama Prefecture, and follows the Median Tectonic Line all the way through the Kii Peninsula, Shikoku, and even into Oita Prefecture.

A Place to Learn About River Stones

Aoiwa Park serves as a field study site for “River Stone Learning,” attracting many elementary, junior high, and high school students every year.

More Than 10 Types of Rocks Can Be Found!

Aoiwa Park is located at the confluence of the Kabura River and the Nanmoku River, and stones carried downstream from both rivers accumulate here. Among the large boulders scattered across the stone pavement, some have diameters exceeding 3 meters. These were likely brought by massive floods, reminding us of the power of nature.

River Stones in Aoiwa Park

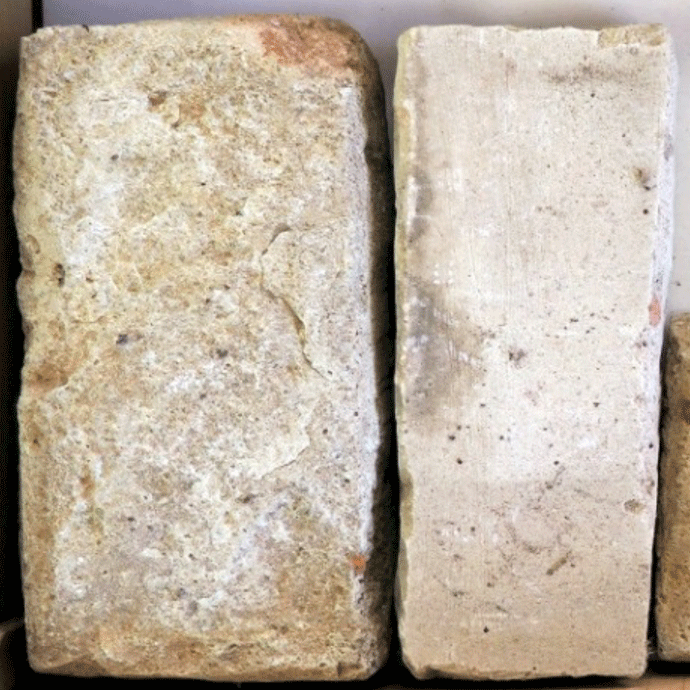

Limestone

White, smooth, and often rounded, these stones are formed either from the remains of marine organisms or from calcium carbonate that precipitated out of seawater.

Because it’s soft, limestone is easily scratched. It is used in fertilizer, erasers, chalk, and cement materials.

Its origin is in the limestone mountains upstream of the Aokura and Nanmoku Rivers.

Greenstone

The green rock, which is a defining feature of Aoiwa Park, is called greenstone.

It is typically green with faint parallel striations. Greenstone forms when rocks are pushed deep underground and undergo metamorphosis under high pressure.

Under even higher pressure, green schist (a type of crystalline schist) is formed. This type of rock is also known as Sanbagawa stone, and it was used to make itabi (stone tablets).

Itabi are a type of stone monument used mainly as memorial or offering towers. They were common from the Kamakura to Muromachi periods and are considered predecessors of modern-day sotoba (wooden memorial tablets).

Chert

Chert is a hard, glossy, and smooth rock with a bumpy surface.

It is composed of the microscopic shells of radiolarians that once lived in the ocean. Historically, it was used as flint for starting fires.

Its origin lies in the upper reaches of the Nanmoku, Aokura, and Kuriyama Rivers.

Chert Wall

12. Suwa Shrine

The deities enshrined at Suwa Shrine are

Takeminakata-no-Kami, Yasakatome-no-Mikoto, and Homudawake-no-Mikoto.

In ancient times, they were revered as gods of hunting and agriculture; during the samurai era, as gods of war; and today, they are venerated as deities of industry, traffic safety, and matchmaking.

The shrine is believed to have been founded about 400 years ago. Originally a Hachiman Shrine, it was converted into a Suwa Shrine during Takeda Shingen’s incursion into Jōshū (present-day Gunma). It is said that Obata Owari-no-Kami, the lord of Obata Castle, invited the deity from Suwa (a process known as kanjō, the transfer of a deity’s spirit to a new location for worship).

The shrine’s magnificent and intricately crafted buildings were constructed between 1837 (Tenpō 8) and 1846 (Kōka 3), during the late Edo period.

The chief carpenter was Yazaki Zenji, a master builder of the Ōsumi school from Suwa in Shinshu (Nagano Prefecture), renowned for temple and shrine architecture. After Zenji’s death, the haiden (worship hall) and heiden (offering hall) were completed by his second son, Yazaki Fusanosuke Akifusa. The main sanctuary (honden) is considered Zenji’s final and most distinguished work, as he passed away in 1841 (Tenpō 12).

Worship Hall Front Carvings

Above the main beam at the front of the worship hall, two dragons are entwined, with one biting the other’s neck. In addition, each of the two side columns and the beam features two dragons spiraling around them.

It is said that such large-scale dragon carvings that entwine both pillars and beams are unparalleled elsewhere in Japan.

Worship Hall Side Panel Carvings

Left side: A parent lion is shown pushing two cubs down a thousand-foot cliff to train them — a traditional motif symbolizing strength and discipline.

Right side: A mythical Chinese lion (karajishi) emerges from a waterfall alongside a magpie and peonies.

Autumn Grand Festival

Every year, on the two days preceding Health and Sports Day (a national holiday in October), the shrine holds its grand autumn festival (Aki Matsuri), a bold and historic celebration that has continued since the Tenpō era.

The event features the Mikoshi Togyo, a ritual in which a portable shrine is carried through the community to pray for protection and well-being, along with a parade of floats (dashi).

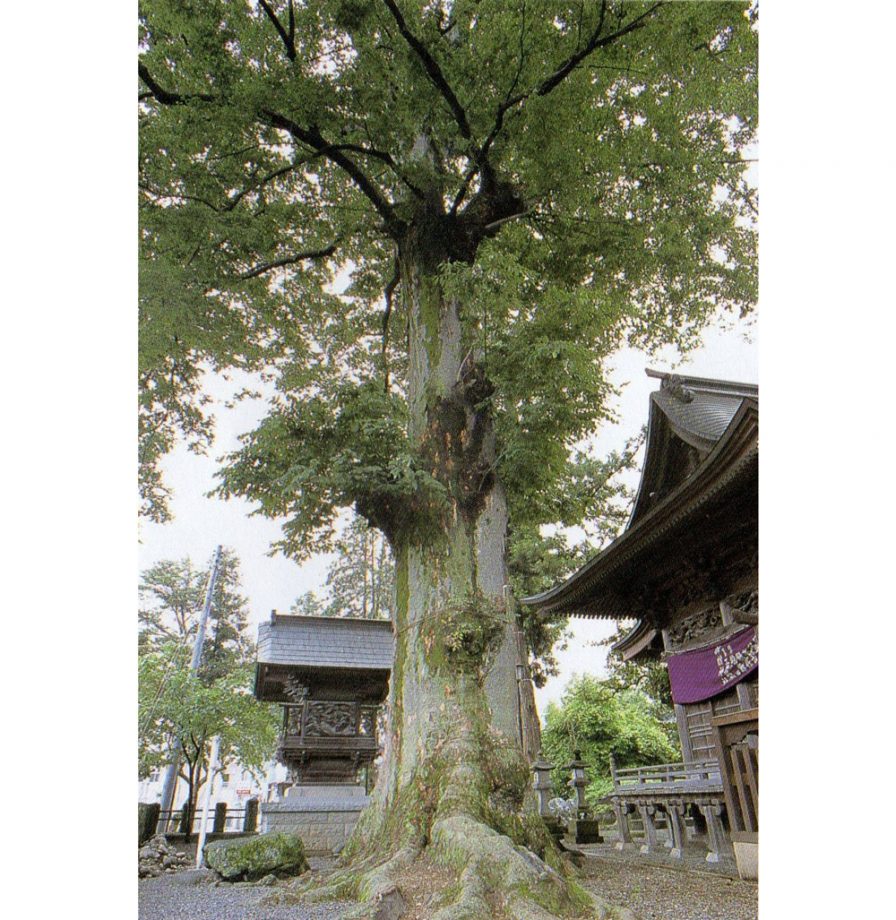

The Great Zelkova Tree

Designated as a Natural Monument by the town of Shimonita, this sacred tree (shinboku) stands 25 meters tall. It is estimated to be 650 years old, with a trunk circumference of 5.5 meters at eye level and a root spread of 7 meters.

Seven Floats Parade!

Floats from seven neighborhood groups take part in the festival parade:

• Kamigumi (Kamimachi)

• Kagumi (Kawai)

• Yogumi (Yoshizaki)

• Nagumi (Nakamachi)

• Shimogumi (Shimomachi)

• Azumagumi (Azumacho)

• Asahigumi (Asahicho)

13. Rootless Mountains (Klippe)

Klippe are isolated mountains that were originally formed elsewhere and later displaced by tectonic forces. These rock layers were pushed over other rock bodies, and after long-term erosion by wind, rain, and rivers, they became separated from surrounding formations.

As a result, the upper layers of a klippe consist of rocks such as the Atogura Formation, which were formed from sediment that accumulated on the seafloor around 130 million years ago. Meanwhile, the lower rocks are younger greenstones (metamorphic rocks) that originated deep underground.

To the south of Shimonita, you can see a range of unusually shaped mountains. These rare formations are known in Japan as “Floating Mountains” or Klippe. Examples include:

• Kamanuki-yama

• Ōyama

• Ontake

• Ōguyama

• Kawai-yama

• Yotsumata-yama

Ontake

This mountain best exemplifies the features of a klippe. The boundary between the upper and lower rock layers can be observed at Hotaru-yama Park. The trail to the park is relatively gentle, but the slope steepens dramatically beyond it.

Along the summit and hiking paths, you’ll find stone monuments and shrines associated with the Ontake faith.

The area up to Hotaru-yama Park consists of greenstone, the same type found in Aoiwa Park. From the steep slope upward, the rock transitions to the Atogura Formation.

Ōguyama

Among the klippe mountains, Ōguyama is the steepest, surrounded by cliffs. It is composed of rock from the Atogura Formation, and near the riverbed, you can observe clear evidence of it being a klippe.

The Atogura conglomerate is known for being easily fragmented on slopes, creating large cliff faces. As a result, the mountain is characterized by sheer cliffs rising all the way to the summit.

The Klippe Slip Surface

In front of the Shimonita Museum of Natural History, you can view an exposed “klippe slip surface.”

At this location, the boundary between two rock layers is visible in the riverbed, exposed by the erosion of the flowing water. These rock layers, which were pushed against each other under intense pressure, have left behind polished surfaces known as kagami-hada (“mirror surfaces”) and grooves called jōsen (“striations”) — both of which are telltale signs of tectonic movement.

14. Iseyama Myoken-son and the Former Kabura River Cliff Line

If you head west from the traffic lights in Shimonita and turn north off National Route 254, you’ll find Iseyama Myoken-son.

Along the approach to the shrine, you can observe the Shimonita Formation, which consists of marine sediments that accumulated around 20 million years ago.

The national road that runs from Shimonita to Shimo-osaka features sharp curves, and the cliffs to the north and east of the road are extremely steep. This area marks the boundary between the mountains and the terrace inland. It is believed that this was once the riverbank of the Kabura River around 30,000 years ago.

15. Upper Terrace and Shimonita Town Historical Museum

The elevated area where the Historical Museum is located is part of a terrace surface from the same period as the upper terrace of Mayama. While the loam layer is not visible, rounded gravels (terrace gravel layer)—once carried by the riverbed of the former Kabura River—can be observed in places along the upper section of the steep walking trail that descends south from the museum.

Kumano Archaeological Site

An archaeological site from the Yayoi period, located on the terrace where the museum stands.

Terrace Landforms

In the Mayama area, Quaternary terrace landforms are clearly visible. The lower terrace, where National Route 254 runs and residential houses are concentrated, lies at a lower elevation.

In contrast, the slightly elevated area to the south is the upper terrace. Over time, this upper terrace has become somewhat uneven due to erosion from wind and rain. A regional agricultural road now runs along this terrace.

16. Lower Terrace: Shimosaka to Shimonita

A low, flat surface extends along the Kabura River. This surface is the lower terrace. In many areas of Shimonita, the lower terrace is where people live today.

The lower terrace was formed approximately 30,000 to 10,000 years ago. In Shimonita, the sediments are shallow, and just beneath them lies the Neogene bedrock.

17. Upper Terrace: Kawai and Tengudaira Ruins

A small flat area lies at a higher elevation than the Kawai settlement, where orchards are cultivated.

This area is also an upper terrace formed around 200,000 to 150,000 years ago. Along the road ascending from below, you can observe terrace gravel layers, with loam layers covering the terrace surface.

This terrace is the site of the Tengudaira archaeological ruins. Artifacts such as Jomon pottery with impressed patterns from the Early Jomon period, and bamboo-pipe pattern pottery from the Middle Jomon period, are exhibited at the local history museum.

18. The Kawai Fault (Median Tectonic Line) and the Shimonita Formation

Median Tectonic Line

Directly beneath Suwa Shrine runs the Median Tectonic Line (MTL)—a major fault system that cuts across Japan from east to west.

The MTL stretches from Oita, through Shikoku and the Kansai region, then heads north at Atsumi Peninsula (Aichi Prefecture), continuing through Inadani and Lake Suwa in Nagano Prefecture, and on to Shimonita.

Shimonita Formation

In Shimonita Town, the geology differs significantly between the southern and northern sides of the Median Tectonic Line.

To the south, you can find greenstone in places like Aoiwa Park.

To the north lies the Shimonita Formation, which is rich in fossilized shell remains, including over 30 species of mollusks, shark teeth, and crab fossils.

These strata represent a marine environment from about 20 million years ago.

Gunma Prefecture Around 20 Million Years Ago

This was the era when the Japanese archipelago began to separate from the continent, forming many small islands. What is now Gunma Prefecture was still beneath the sea.

The ocean around Japan at the time was warmer than it is today and was home to creatures such as dolphins, whales, and dugong relatives.

Fossils of large mammals have also been found in Tomioka City and Annaka City.

19. Konjac Waterwheels and Powder Refining

The Tajimaya Konjac Refinery operated from 1926 (Taisho 15) to 1998 (Heisei 10). In its early years, it used traditional Japanese wooden waterwheels, and from around 1935 (Showa 10), it switched to turbine waterwheels, which powered 112 pestles used for refining konjac powder.

Today, the waterwheels have been removed, but the remains of the water channels, the shed, and the pestles and millstones can still be seen.

Downstream from the confluence of the Kabura River and the Nammoku River, the river widens and flows more gently, making it unsuitable for waterwheel construction.

In contrast, the upstream area features a narrow river channel and steep terrain, resulting in a swift current—ideal conditions for waterwheel power.

At its peak, there were waterwheels spaced approximately every 100 meters upstream from the confluence. The Aokura River had 8 waterwheels within a 2-kilometer stretch, while the Kuriyama River had 5 waterwheels within 1 kilometer.

Konjac Waterwheels

In the mid-Edo period, in Kuji District, Ibaraki Prefecture, Toemon Nakajima invented a method for refining konjac corms into powder.

Later, in 1876 (Meiji 9), Kumekichi Shinohara from Tomioka witnessed konjac corms being sliced and processed during a business trip. Wanting to bring the technology to his home region, he returned with Shuzo Saito, and together they modified a wheat-milling waterwheel in Ozawa Village (now part of Nammoku Village), creating the first konjac waterwheel.

References

• Shimonita Town Official Website (Shimonita Town, 2019)

• Shimonita Town History (Shimonita Town, 1971)

• Shimonita Guidebook (Shimonita Tourism Division, 2016)

• The Shimonita War Record (Shimonita Board of Education)

• The Shimonita Road (Gunma Prefectural Board of Education, 1981)

• Architectural Carvings of the Suwa Shrine in Shimonita (Shimonita Chamber of Commerce, 2010)

• Merchants’ Guide for Provincial Travels (Miyama Library, 1990)

• Gunma History Walk No.183 (Gunma Rekishi Sanpo Association, 2004)

• Kosakasaka Pass Road (Kosakasaka Old Road Research Society, 1995)

• 100-Year History of the Joshin Railway (Joshin Railway Co., Ltd., 1995)

• Geology of Shimonita and Surrounding Areas (Shimonita Nature School, 2009)

• The Road History of Japan Vol.17: Nakasendo (Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2001)

• The Story of Konjac Waterwheels in Shimonita (Takashi Harada, 2019)